|

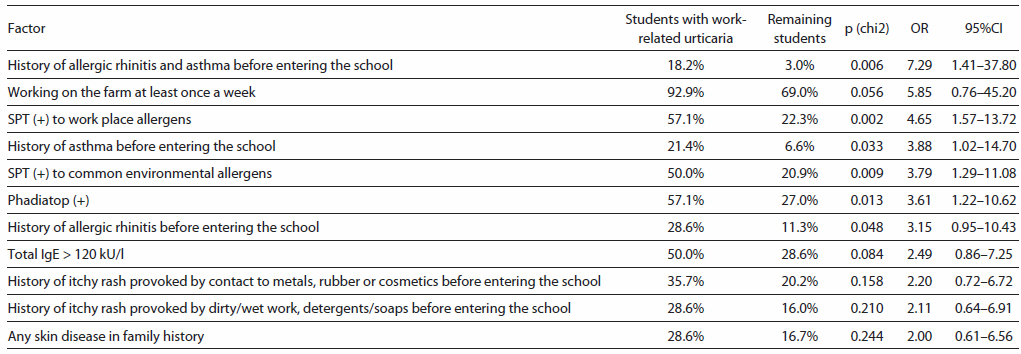

Introduction and objective: Farmers are at high risk of occupational skin diseases which may start already during vocational training. This study was aimed at identification of risk factors for work-related skin diseases among vocational students of agriculture. Material and methods: The study involved 440 students (245 males, 195 females aged 17-21 years) in 11 vocational schools which were at least 100 km from each other. The protocol included a physician-managed questionnaire and medical examination, skin prick tests, patch tests, total IgE and Phadiatop. Logistic regression model was used for the identification of relevant risk factors. Results: Work-related dermatoses were diagnosed in 29 study participants (6.6%, 95%CI: 4.3-8.9%): eczema in 22, urticaria in 14, and co-existence of both in 7 students. Significant risk factors for work-related eczema were: history of respiratory allergy (OR=10.10; p<0.001), history of eczema (itchy rash) provoked by wet work and detergents before entering the school (OR=5.85; p<0.001), as well as history of contact dermatitis to metals, rubber or cosmetics prior to inscription (OR=2.84; p=0.016), and family history of any skin disease (OR=2.99; p=0.013). Significant risk factors for work-related urticaria were: history of allergic rhinitis and asthma prior to inscription (OR=7.29; p=0.006), positive skin prick tests to work place allergens (OR=4.65; p=0.002) and to environmental allergens (OR=3.79; p=0.009), and positive Phadiatop test (OR=3.61; p=0.013). Conclusions: Work-related skin diseases are common among vocational students of agriculture. Atopy, past history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema (either atopic, allergic or irritant) are relevant risk factors for work-related eczema and urticaria in young farmers, along with family history of any skin disease. Positive skin prick tests seem relevant, especially in the case of urticaria. Asking simple, aimed questions during health checks while enrolling students into agricultural schools would suffice to identify students at risk for work-related eczema and urticaria, giving them the chance for selecting a safer profession, and hopefully avoiding an occupational disease in the future. Keywords: work-related dermatoses, occupational skin disease, risk factors, farmers, agriculture, vocational schools, apprentices, eczema, dermatitis, urticaria. |

Compared to most other professional groups, farmers are at high risk of occupational skin diseases [1, 2]. Although farmers in Finland comprise only 7% of the total workforce, they amount to 21% of all workers with acknowledged occupational skin disease (OSD) [2]. The incidence of OSD among farmers is four times higher than the mean incidence in non-farming occupations, and forty times higher than occupational respiratory diseases [3]. These data hint about the need for better prophylactic measures in this occupational group. Early identification and counselling those at risk appears to be one of the mainstays of effective prevention. Arguably, this should take place before undertaking the profession, or better still - before starting vocational education, to give the individuals at risk the possibility of avoiding high-risk professions. Large-scale intervention, a pre-employment medical assessment, should consist of no more questions and tests than necessary and relevant to the specific occupation [4]. Unfortunately, evidence for the effectiveness of a pre-employment health check is still lacking for most occupations [5, 6, 7].

The aim of the study was to assess the frequency of work-related skin diseases among vocational students of agriculture, as well as to identify relevant risk factors for the development of these diseases. Special attention was paid to the history of allergic diseases before starting the education, as well as to the value of allergy tests while identifying persons at risk.

Participants for this cross-sectional study were recruited in eleven Polish vocational schools offering curricula in agriculture or farming. To ensure a good geographical coverage, the schools were at least 100 km from each another. The distribution of the schools was intended to reflect the distribution of farmers in Poland [8]. In each school, all final year students in agriculture or farming were invited to participate in the study. In order to avoid selection bias (e.g. students with health problems being more interested in participating than those who were healthy), the precondition for visiting a given school was that at least 90% of all eligible students would agree to take part in the study. This precondition was fulfilled in all invited schools. All participants were examined within a 12-month time window. Each participant received information about the aims of the study and gave written consent to participate. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Rural Medicine in Lublin. The students underwent medical examinations by a medical team which included a board-certified dermatologist, an internist, and an ENT-specialist who participated in order to verify diagnoses of allergic asthma and rhinitis which were among the analysed tentative risk factors for work-related skin diseases. The examinations included a physician-administered questionnaire (available at www.sensiquest.com), based upon two previously validated questionnaires [9, 10]. Skin prick tests (SPT), spirometry, anterior rhinoscopy, total IgE and Phadiatop (Phadia, Sweden) were performed in each study participant. Common allergens used in SPT were: house dust mite Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, animal dander mix I, grass/cereals pollen mix, tree pollen mix I, tree pollen mix II and weed pollen mix (Allergopharma, Germany). The farm work-specific allergens included storage mites Acarus siro, Lepidoglyphus destructor, Tyrophagus putrescentiae, cow epithelium, pig epithelium, horse epithelium and hay dust (Allergopharma), as well as grain dust, straw dust, and hay dust (Biomed, Poland), in line with previous research [10] and availability of commercial allergen preparations at the time of the study [11]. Each school was visited once, a follow-up was not attempted as the participants were last-year vocational students who were about to leave the schools through which they were recruited.

Atopic eczema (AE) was diagnosed using criteria by Hanifin and Rajka, diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) was based upon the clinical history and clinical finding, along with relevant contact allergy confirmed in patch tests, while irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) was diagnosed in cases of eczema of skin areas exposed to known irritants. Patch tests were performed in all cases of suspected contact dermatitis, except in cases where history clearly indicated on the sensitizer (e.g. earlobe dermatitis due to earrings or eczema at the site of applying a cosmetic). Due to the limitations of the field study, patch tests were performed with a short series of ten substances mounted in IQ Ultra test unit (Chemotechnique Diagnostics, Sweden), with only one reading carried out two days after application; in all other aspects the tests followed standard procedures [12].

The selection of haptens, based on a previous study [13], included nickel sulfate 2.5% pet., cobalt chloride 1% pet., potassium dichromate 0.5% pet., fragrance mix I 8% pet., mercuric chloride 0.1% pet., neomycin sulfate 20% pet., thimerosal 0.1% pet., mercapto mix 1% pet., black rubber mix 0.6% pet., and Myroxylon pereirae 25% pet. (Chemotechnique Diagnostics). Diagnosis of urticaria was based on characteristic clinical symptoms (presence of pruritus and wheals).

In further analyses, work-related skin diseases were diagnosed if eczema (dermatitis) or urticaria symptoms recurred following every (or almost every) exposure to a specific factor during farm work. Only diseases that would cause considerable limitations to daily work routines were taken into account - in the case of eczema (a more chronic ailment), it had to limit normal activities and persist for at least two days. For urticaria, the requirement was that symptoms would force the affected person to cease the work, no criterion of duration was set with regard to this disease, which may be a recurrent, yet short-lasting phenomenon. The term "point prevalence" refers to disease symptoms present at the time of medical examination, "1-year prevalence" refers to disease symptoms present in the year preceding the examination (including the moment of examination), while "lifetime prevalence" referred to symptoms present at any time point in life, including the two previously defined periods.

In order to study possible risk factors for the development of work-related skin diseases, participating students were asked about details from their medical history before and after starting education at the agricultural school. Altogether, 144 variables were collected and analysed for every student. T-test was used for the comparison of the frequency of type I allergy to plant dusts among students with and without work-related skin diseases. Chi-square test and logistic regression were used for the assessment of the relationship between intensity of work on the farm and the prevalence of skin symptoms provoked by plant dusts, as well as for the comparisons of prevalence rates of potential risk factors among students diagnosed with work-related skin diseases and the remaining students. Odds ratios with confidence intervals were also calculated. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 11.2 (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was regarded as significant.

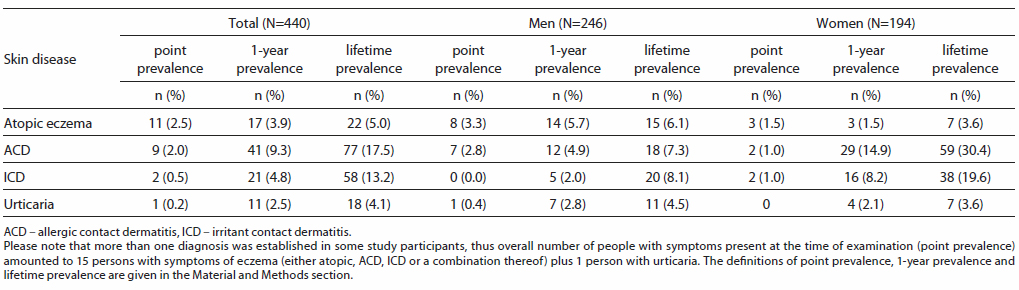

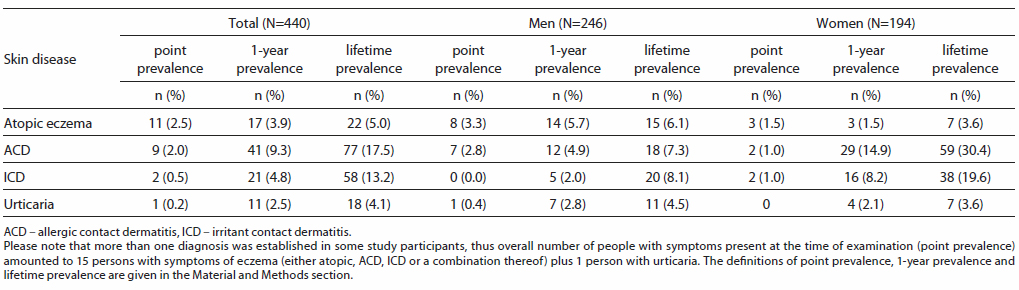

A total of 440 vocational students from eleven agricultural schools participated in the study: 245 males and 195 females, aged from 17-21 (median 18) years. The prevalence rates for skin diseases of interest for this study (either workrelated or not) are shown in Table 1, comorbidities were relatively frequent. Among fifteen students (3.4%, 95%CI: 1.7-5.1%) with eczema (ultimately diagnosed as either atopic, ACD, ICD, or a combination thereof) present at the time of examination, predominant involvement of uncovered skin areas was recorded in eight (1.8%, 95%CI: 0.6-3.1%), sole or main involvement of the hands in 6 (1.4%, 95%CI: 0.4-2.4%), and generalised eczema in one person (0.2%, 95%CI: 0.0-0.7%). One person presented symptoms of urticaria at examination, which consisted of a few itchy wheals on the forearms.

|

Skin problems provoked by work on the farm were reported by 129 study participants (29.4%, 95%CI: 25.1-33.7%). The leading cause of skin symptoms was grain dust, which was indicated by 115 (26.1%) students, followed by hay dust (12.8%), straw dust (6.8%), fertilizers (6.7%), pesticides (3.3%), work in cowsheds (2.2%) and horse stables (1.6%), as well as machinery reparations (1.5%). Working more frequently on the farm appeared as a risk factor for developing skin symptoms due to grain dust (Tab. 2). All students experiencing skin symptoms provoked by grain dust (N=115) complained of pruritus (100%), followed by erythema (54.8%), papules (25.2%), wheals (15.7%), burning sensation of the skin (4.3%), scaling (3.5%), vesicles and oedema (each 2.6%). Interestingly, twenty-six (22.4%) of these 115 students with such skin symptoms also complained of dyspnoea, wheezing or chest tightness provoked by grain dust. All dust-related skin symptoms were reportedly located on uncovered skin areas, except in three students who indicated involvement of the entire body.

|

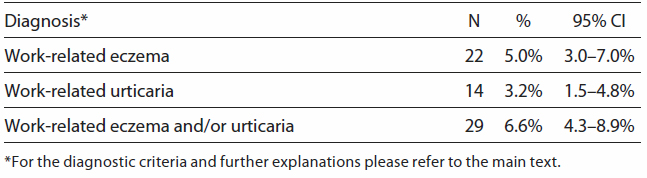

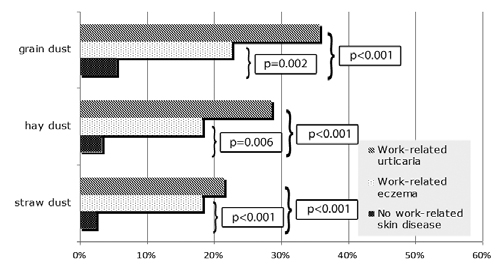

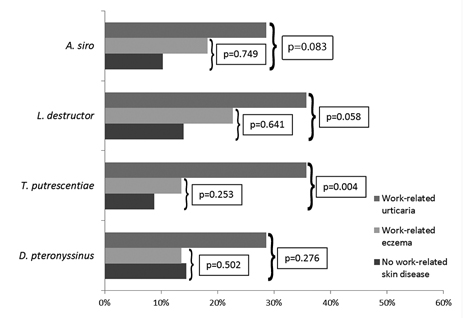

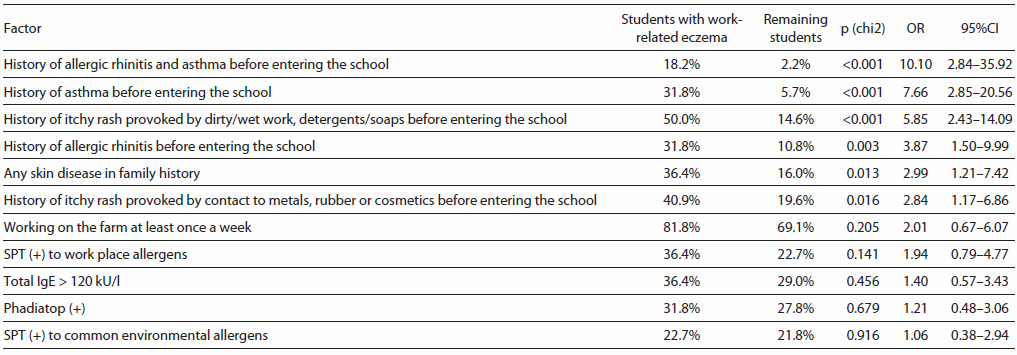

Altogether, twenty-nine cases were identified of workrelated skin diseases that would interfere with daily activities (Tab. 3). Among twenty-two students with work-related eczema (at present or based on past medical history), nine had positive reactions in skin prick tests (SPT), including eight (36%) students reacting to at least one farm allergen: five each to L. destructor and grain dust, four each to A. siro, straw dust and hay dust (Allergopharma), three to T. putrescentiae, two to hay dust (Biomed), and one to pig epithelia. Among fourteen students with work-related urticaria, positive reactions on SPT were observed in eight (57%); all reacted to at least one work-related allergen: five each to L. destructor, T. putrescentiae, grain dust and hay dust (Biomed), four each to A. siro and hay dust (Allergopharma), three to straw dust, and one each to pig and horse epithelia. Type I allergy to grain, hay and straw dust was significantly more frequent among students with work-related urticaria (respectively, 35.7%, 28.6%, 21.4%) and eczema (22.7%, 18.2%, and 18.2%) than among those without work-related skin problems (5.4%, 3.2%, 2.4%) (Fig. 1). With regard to storage mites (A. siro, L. destructor, T. putrescentiae) and house dust mite D. pteronyssinus sensitization, the respective figures were again higher for work-related urticaria (respectively 28.6%, 35.7%, 35.7%, and 28.6%) and work-related eczema (18.2%, 22.7%, 13.6%, and 13.6%) than for the remaining students (10.2%, 13.9%, 8.7%, and 14.4%). However, most observed differences were not statistically significant except for T. putrescentiae allergy in work-related urticaria, and the results for A. siro, L. destructor were close to the assumed significance level (Fig. 2). Results of the analysis of risk factors for the development of work related eczema and urticaria are shown respectively in Tables 4 and 5.

|

|

|

|

|

The difficulty in differentiating between various forms of diseases from the spectrum of dermatitis/eczema and resulting problems with the reliability of epidemiological data has been recently discussed elsewhere, with the conclusion that differential diagnosis is difficult and can be easily biased by the beliefs and expectations of researchers [14]. Therefore, in the presented study of work-related skin diseases, it was decided to use the terms "eczema" or "urticaria" because a detailed insight into the underlying mechanisms was not always possible in the setting of a field study. Airborne dermatitis caused by grain dust may be either irritant or allergic - differentiation between these two diagnoses would not be possible without exposing the participants to the dusts and observing the morphology and dynamics of skin response over a period of several days. For the same reason, when analysing the history of contact dermatitis before entering the school as a tentative risk factor for work-related skin diseases, differentiating between ICD and ACD would be hardly possible based merely on the patient's history, even for a specialist. Such an "academic" approach would prove even less feasible for an aspiring student and a school doctor carrying out the prospective pre-enrollment health check. Instead, a simple approach was adopted focusing on the factors provoking relapses or aggravations of eczema: Dermatitis provoked by agents with relatively low irritant properties (e.g. leave-on cosmetics, rubber, jewellery) was considered as a hint for ACD, whereas aggravations predominantly due to known irritants (e.g. detergents and soaps, wet and dirty work) was hinting on possible ICD. A considerable weakness of such a division is that in many cases of ACD, the diseased skin will also be susceptible to irritants; on the other hand, "mild" cosmetics may exert irritant effects, especially on the skin already affected by ICD. Therefore, a considerable overlap of ACD and ICD should be taken into account [14]. In the presented study, comparable frequencies were found of physician-diagnosed atopic eczema and contact dermatitis with a considerable overlap of both diseases, which is in line with previous results in Polish teenagers (16-17 y.o.) [15]. The prevalence of hand eczema at the time of medical examination found in this study (point prevalence 1.4%) was similar to the rates observed in other occupational groups in Poland (1.9%) [16]. These figures were, however, considerably lower than the point prevalence of 5.8% found among Finnish farmers [17]. This discrepancy might be explained by the older age, as well as possible differences in exposures, working habits and genetic background of Finnish farmers, as well as different criteria for diagnosing hand eczema.

The prevalence of self-reported urticaria in the current study was higher than previously observed in a random sample of Polish adults (4.1% vs. 2.8%) [18]. Interestingly, 57% of the students with work-related urticaria were found with type I allergy to occupational allergens (Tab. 5), which stands out, taking the rarity of allergic aetiology of urticaria in general. The significantly higher frequency of plant dust allergy among students with work-related urticaria (Fig. 1) and the relatively high coincidence of grain dust-related skin disease with respiratory symptoms, may hint on systemic allergy, the same as in contact urticaria syndrome. Single cases of immunological contact urticaria caused by cereal allergens have been reported previously [19]. Nevertheless, concomitant irritant reaction of the skin and airways to the dust without involvement of immune mechanisms cannot be excluded in some cases.

Farmers are exposed on a day-to-day basis to an array of sensitizers and irritants [4]. Agrochemicals - disinfectants, pesticides, petrol, etc. - seem to gain more attention [20], possibly because of their perception as "contaminants" in contrast to "natural" compounds of plant and animal origin. As a matter of fact, plants are among the most prominent sensitizers in the agricultural environment [21]. In the present study, plant dusts were the dominating cause of work-related skin symptoms and diseases - indicated by respondents most frequently as provoking factors, and also caused by far more positive reactions in skin prick tests. This is in line with previous findings in hop growers, of whom 19.2% complained of work-related skin symptoms, most frequent caused by exposure to hops (indicated by 11.0%), grain dust (5.6%), hay dust (5.5%) and straw dust (4.1%) [22]. As many as 8.7% farmers occupationally exposed to thyme dust developed airborne dermatitis within thirty minutes of work [23]. The relevance of "food" allergens of crop plants as occupational airborne skin sensitizers has been demonstrated on the examples of wheat and rye flour, which does not seem to differ substantially from milled grain used as animal food [24].

Plant dusts are complex materials containing variable amounts of allergens, haptens, and irritants, as well as live microbes and their products, which also seem to play a role in the pathogenesis of work-related skin diseases. In a group of young farmers with cellular reactivity to antigens of bacteria and fungi colonizing crop plants, all had complained of work-related skin symptoms; moreover, they were diagnosed with dermatitis four times more frequently than farmers with no specific reactivity to these antigens [25]. Cell wall components of Pantoea agglomerans - common airborne bacteria in farm environment, stimulate human leukocytes to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α, which may serve as a "danger signal" initiating sensitization to otherwise harmless environmental allergens and haptens [26]. Type I allergy to livestock animals was infrequent and seemed of little importance in the present study group, which is in line with previous observations [8]. Nevertheless, in individual cases, specific sensitization to animal allergens may predict the development of occupational eczema or urticaria [27]. The notion that organic dusts commonly associated with respiratory diseases) are frequent causes of skin disease, together with the observation that haptens (commonly associated with allergic contact dermatitis) may cause occupational asthma, demonstrates that there are no clear-cut divisions between allergic mechanisms and phenotypes.

Despite representing a significant economic burden for the public health system, occupational skin diseases are still not adequately taken care of at national and European level, due to lack of awareness among patients, physicians and regulators, insufficient and inadequate safety and health legislation, patients' fear of job loss, as well as lack of time and motivation [28]. Work-related exposures in agriculture are extremely complex and difficult to measure, while diseases from the spectrum of eczema are hard to differentiate and frequently overlap. As a result, mechanisms of work-related eczema caused by agricultural dusts remain obscure and require more dedicated studies. Nevertheless, irrespective of the mechanisms involved, the results obtained during the presented study indicate that people at risk for work-related eczema may be relatively easily identified by asking a few aimed questions, while "predictive" allergy tests seem of questionable relevance (Tab. 4). In the case of work-related urticaria, allergy tests would probably provide some useful information, although asking right questions would be still of the utmost importance (Tab. 5). The presented results suggest that atopy (understood as either positive skin prick tests or history of allergic respiratory disease) is a relevant risk factor for work-related skin diseases in young farmers. The frequency of positive tests to farm allergens in this group may be partly explained by the fact that the majority of the students were born and raised on a farm, or have worked on a farm from an early age as family help or hired workforce. Thus, for most of them, exposure to future occupational sensitizers began in childhood. Early development of allergy to farm antigens was also observed among young Austrian farmers [29]. Regardless of the final decision as to whether to include "predictive allergy tests" into the pre-enrolment health check, it seems that adding relevant questions from Tables 4 and 5 would certainly improve the effectiveness of health checks at entry to agricultural schools. The identification of individuals at risk would allow for an appropriate early start of primary prevention, including pre-employment counselling and implementation of technical and organisational measures to prevent the development of the disease [30], or give them a chance to re-consider their choice and possibly opt for another, safer vocation. The long-term effectiveness of such preventive measures is difficult to quantify and more research is needed in this field [7].

The study showed that work-related skin diseases are relatively common among vocational students of agriculture. Atopy, along with past history of asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema (either atopic, allergic or irritant) are relevant risk factors for work-related eczema and urticaria in young farmers, together with a family history of any skin disease. Positive skin prick tests to occupational allergens seem to be of some relevance in urticaria. In either case, asking simple, aimed questions during health checks before enrolling students into agricultural schools would suffice to identify students at risk for work-related eczema and urticaria, giving them the chance to select a safer profession, and hopefully avoid an occupational disease in the future.

© Radoslaw Spiewak (contact).

This page is part of the www.RadoslawSpiewak.net website.

Document created: 21 December 2017, last updated: 4 October 2019.